There is a lot of talk these days about misinformation, disinformation and outright lies on the internet. And about whether or not sites like Facebook and Twitter should be exercising greater vigilance about what they allow to be posted. Recently I’ve read several articles in the New York Times reporting that platforms like Facebook and Twitter have reduced their oversight staff, in some cases to one manager and only five or six people. Given the number of users ― and abusers ― of these sites, that’s an astonishing dereliction of duty.

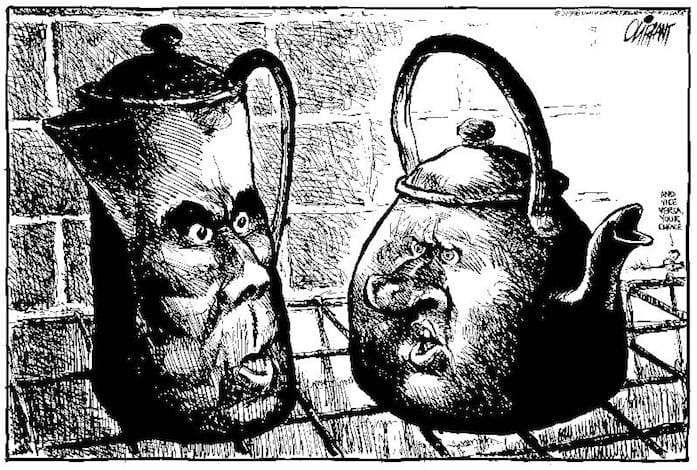

Alas, this isn’t a problem just for politics or the “culture wars” promoted by right-wingers across the globe. It’s a problem for academics too. On Feb. 15, 2023, Luca Bianchini ― the Donald Trump of Mozart studies ― made some pretty outrageous claims in a Facebook post concerning some aspects of my edition of the Mozart family letters, and in particular the letters from Italy (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 2019). Bianchini writes that I not only don’t know how to use primary sources but that I deliberately ignore, mistranslate or quote piecemeal any source not corresponding to my preconceived ideas about Mozart [“Se una fonte non gli piace, Cliff Eisen la ridicolizza, la cita a spizzichi e mozzichi, la traduce male o addirittura l’ignora pur di conformarla alle sue idee”.] This seems to me to be an application of the popular trope about the-pot-calling-the-kettle-black. He cites, for example, Maria Theresia’s well-known letter to Archduke Ferdinand in Milan:

“. . . you ask me to take the young Salzburger into your service[.] I do not know why, not believing that you have need of a composer or of useless people[.] If however it would give you pleasure, I have no wish to hinder you[.] what I say is intended only to prevent your burdening yourself with useless people and giving titles to people of that sort[.] If they are in your service it degrades that service when these people go about the world like beggars[.] besides, he has a large family.”[1]

Bianchini claims that «La sua lettera è considerata da Eisen “offensiva e priva di riscontro” e perciò ignorata. Frasi del genere vanno infatti contro la sua idea preconcetta che Mozart sia un dio.» And he further states, as if it’s some sort of justification, that she wrote «la lettera al figlio dopo l’esito fallimentare della Finta semplice di Mozart a Vienna nel 1768 e del Mitridate a Milano del 1770. Dice quelle cose a ragion veduta. Mozart non era un dio.» [sic!]

Bianchini is right about one thing: Maria Theresia’s letter to Ferdinand postdates Mozart’s most recent trip to Vienna, the problems with La finta semplice, and the performance of Mitridate. This is a powerful observation, claiming that a later event happened after an earlier one. It takes a really astute historian to make observations like this. And what about the rest of what he writes?

Let’s start with the claim that I ignore the letter. Hardly. It’s cited on page 241 footnote 3 of my edition. I don’t quite see how including its Mozart-related passage in full is consistent with Bianchini’s claim that I ignore it. As for the suggestion that I consider the letter “offensiva e priva di riscontro” ― note that Bianchini includes “offensiva e priva di riscontro” in quotation marks as if he is citing my words ― here’s what I write about it in the footnote:

Si ritiene che il passaggio si riferisca alle speranze di Leopold di ottenere un incarico fisso alla corte dell’arciduca Ferdinando. Alla fine non se ne fece nulla, verosimilmente a causa – almeno in parte – di una lettera che Maria Teresa scrisse a Ferdinando il 12 dicembre 1771: «[…] mi domandate di prendere al vostro servizio il giovane salisburghese. Non ne vedo il motivo, non credo che abbiate bisogno di un compositore o di gente inutile. Se tuttavia vi fa piacere non voglio impedirvelo. Quello che dico è solo volto a evitarvi di assumere gente inutile e di conferire dei titoli a persone di questo tipo. Se questa gente è al vostro servizio lo sviliscono quando vanno in giro per il mondo come mendicanti. Inoltre, costui ha una famiglia numerosa» (MDL, cit., p. 124). Le ragioni di una tale animosità da parte di Maria Teresa non sono chiare, poiché tutti i resoconti di Leopold circa i loro incontri precedenti erano stati positivi. Si veda la sua lettera del 16 ottobre 1762, in cui descrive un incontro alla corte di Schönbrunn: «[…] fummo ricevuti dalle loro maestà con un favore così straordinario, che, quando lo racconterò, lo si crederà una favola. Basta! il Wolferl saltò in grembo all’imperatrice, le gettò le braccia al collo e la baciò con trasporto»; e quella del 23 gennaio 1768, mentre erano di nuovo a Vienna: «Non posso però fare a meno di dirle che è inimmaginabile la confidenza con cui Sua Maestà l’Imperatrice si è rivolta a mia moglie, intrattenendosi con lei ora sul vaiolo dei miei figli ora sulle circostanze del nostro lungo viaggio etc.; le ha accarezzato il viso e le ha stretto le mani». [2]

I’m not sure I see the words “offensiva e priva di riscontro” here. Rather, I put Maria Theresia’s letter in the context of Leopold’s earlier comments about the family’s perceptions of her, which justifies the use of the word “animosity,” a fair and neutral description of Maria Theresia’s letter: it’s obviously hostile to describe the Mozarts as “useless.”

Bianchini’s defense of Maria Theresia is that she knew Mozart ― wow! claiming to have met someone really explains things! ― that she was aware of the La finta semplice fiasco and, he alleges, the failure of Mitridate. What he doesn’t note is that Maria Theresia had nothing to do with La finta semplice, that Joseph II appears to have defended Mozart on that occasion, and that the cabal against the composer was the work of the theatre intendant, Giuseppe Affligio. As for the “failure” of Mitridate, I guess Bianchini isn’t aware of the review published in the Gazzetta di Milano for 2 January 1771 (also cited in my edition, Bianchini could have read it there, together with the letter he claims I ignored): ‘On Wednesday last the Teatro Regio Ducal[e] reopened with the performance of the drama titled Mitridate, Re di Ponto, which has proved to the public’s satisfaction as much for the tasteful stage designs as for the excellence of the Music and the ability of the Actors. Some of the arias sung by Signora Antonia Bernasconi vividly express the passions and touch the heart. The young Maestro di Cappella, who has not yet reached the age of fifteen, studies the beauty of nature and exhibits it adorned with the rarest of Musical graces.’ [3] In any case, why cite Mitridate at all? The opera was nearly a year old by the time Maria Theresia wrote to Ferdinand in December 1771 and there was a more recent work ― and one more directly related to the imperial family ― for her to pick on if she chose: Ascanio in Alba, composed for the wedding of archduke Ferdinand and Maria Beatrice Ricciarda d’Este in October 1771. Unfortunately for Bianchini, though, Ascanio was also a success. The Notizie del Mondo (Florence) for 26 October 1771 reported that: ‘The opera [Hasse’s Il Ruggiero] has not met with great success and only a single ballet was performed. The serenata [Ascanio in Alba], however, has met with great applause, both for the text and for the music.’ [4]

This report was widely circulated and reprinted with minor changes, for example, in the Diario Ordinario (Rome) for 2 November 1771 and in German in the Staats- und gelehrte Zeitung des Hamburgischen unpartheyischen Correspondenten for 13 November 1771. Similarly, the Wienerisches Diarium for 6 November reported: ‘Milan 12 October. Today, finally, was the masquerade of the so-called Facchini, the magnificence of which evoked general admiration, just as the Serenata received universal applause for its composition and very excellent music.’[5]

So much for knowing the sources and mistreating them. And for reporting accurately and fairly what others have in fact said. Really, there ought to be a law against this sort of things, this apparently deliberate out-and-out fabrication of untruths and misrepresentions. I’m now going to write Nick Clegg at Facebook and alert him to Bianchini’s posts but I doubt he’ll do anything about them. If Facebook is prepared to let Trump post, I suppose they’ll let the academically egregious Bianchini post too.

(edit and footnotes: Carlo Vitali)

====

[1] Otto Erich Deutsch, Mozart. A Documentary Biography (2nd edition) Stanford: University Press, 1966, p. 138. French original: “Vous me demandez de prendre à votre service le jeune salzbourgeois. Je ne sais comme quoi, ne croyant pas que vous ayez besoin d’un compositeur ou de gens inutiles. Si cela pourtant vous ferait plaisir, je ne veux pas vous en empêcher. Ce que je dis est pour ne pas vous charger de gens inutiles et jamais des titres à ces sortes de gens à votre service. Cela avilit le service quand ces gens courent le monde comme des gueux. Il a en outre une grande famille”. (Alfred von Arneth, ed., Briefe der Kaiserin Maria-Theresia an ihre Kinder, Wien: Braumüller, 1881: T. I, p. 92). In fact, the Mozarts were just four persons: father, mother and two siblings; hardly a ‘large family’ by period standards.

[2] Original German: “wir von den Maÿestetten so ausserordentlich gnädig sind aufgenohmen worden, daß, wenn ich es erzehlen werde, man es für eine fabl halten wird. genug! der Wolferl ist der Kaÿserin auf die Schooß gesprungen, sie um den Halß bekommen, und rechtschaffen abgeküsst”. (To Johann Lorenz Hagenhauer, Bauer-Deutsch n. 34); “Überhaupts muß ich nur sagen, daß Sie sich unmöglich vorstellen können, mit was für einer Vertraulichkeit S:e Maÿestätt die Kaÿserin mit meiner Frau sprach und sich theils wegen den Blattern meiner Kinder, theils wegen den Umständten unserer grossen Reise etc. unterhielt; sie im Gesicht über die Wangen strich, und beÿ den Händen drückte”. (To the same, Bauer-Deutsch n. 124)

[3] Original Italian: “Mercoledì scorso si è riaperto questo Regio Ducal Teatro colla rappresentazione del Dramma intitolato il Mitridate, Re di Ponto, che ha incontrata la pubblica soddisfazione sì per il buon gusto delle Decorazioni, quanto per l’eccellenza della Musica, ed abilità degli Attori. Alcune Arie cantate dalla Signora Antonia Bernasconi esprimono vivamente le passioni, e toccano il cuore. ll giovine Maestro di Cappella, che non oltrepassa l’età d’anni quindici, studia il bello della natura, e ce lo rappresenta adorno delle più rare grazie Musicali”.

[4] Original Italian: “L’Opera non ha avuto grande incontro, e non è stato eseguito che un solo ballo. Grande applauso però ha avuto la serenata e per la composizione, e per la musica”.

[5] Original German: “Heute erfolgte endlich die Maskerade der sogenannten Facchini, welche ihrer Prächkigkeit wegen eine allgemeine Bewunderung erregte, so wie auch die Serenata wegen der Composition und ausgesuchtesten Musik den Beysaß aller Anwesenden erhalten hatte”.

8 Marzo 2023 il 20:48

I have read the above article and am somewhat stupefied by Bianchini & Co. But, at the same time, I am fully aware that there exist people today who claim the earth is a mere 4,000 years old, and that a few but very limited number of scientists fail to adhere to the theory of evolution. In other words, it is a given that there are “ outliers” in every field. They draw attention to themselves by attacking others in a reckless manner, debunking well-accepted doctrines and proposing nearly absurd ideas. In its barest form, this no more than a slightly disguised form of marketing, to ga in readership. However I only wish that it could be as amusing and original as the “pet rock”craze — which made millions in America off of a silly idea. It was so absurd that people actually liked it and offered to pay money for a rock in a box. I have yet to read of any well known Mozart scholars who have taken a similar liking to Bianchini’s antics, ideas and theories. Perhaps 4,000 years from now, it might actually be up for consideration…